The International Guide for Local Decision-Makers

*This guide was developed at the beginning of 2020 and in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, before any treatments or vaccines were available.

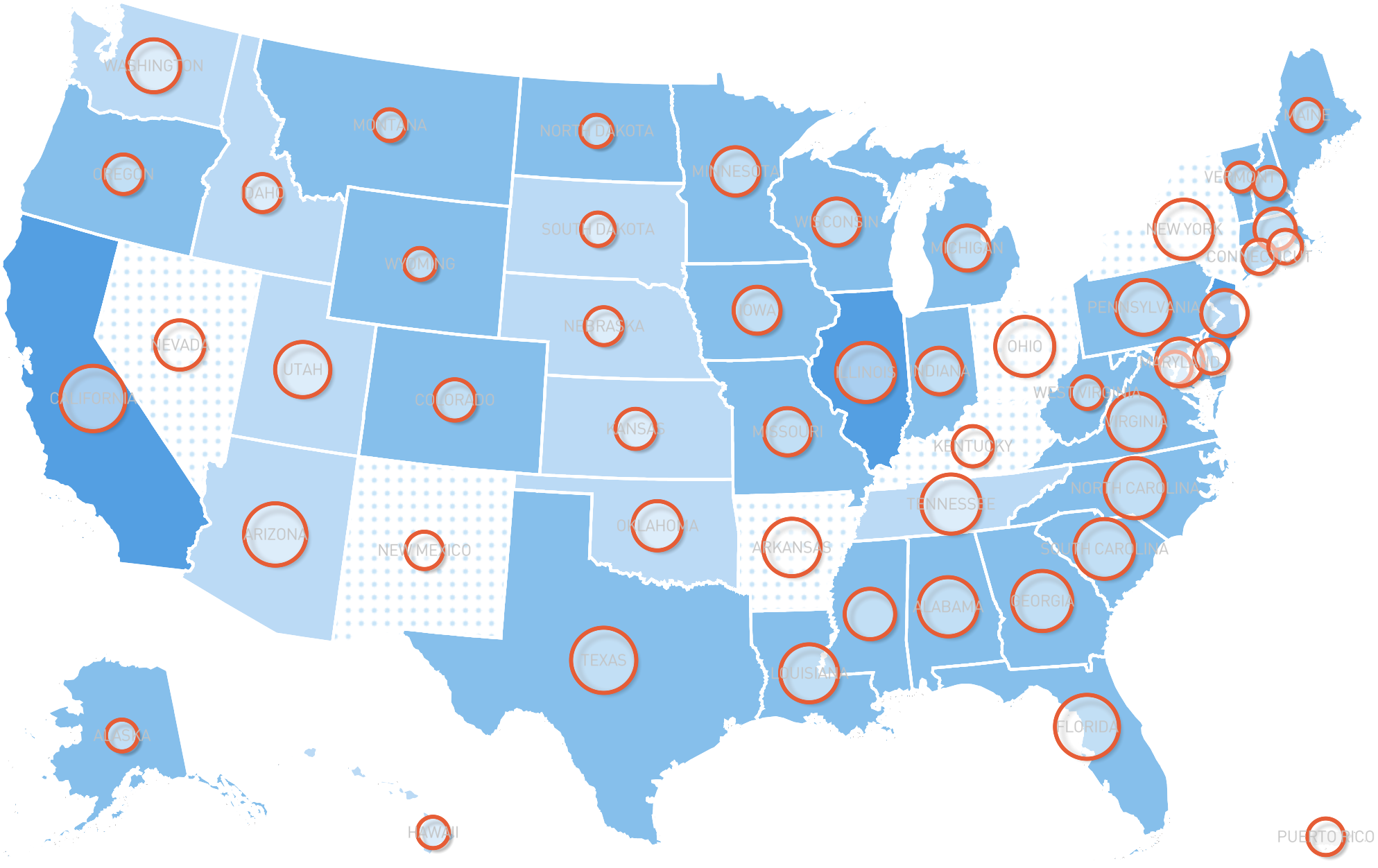

The COVID-19 pandemic is disrupting daily life in communities around the world. This guide provides an initial strategic framework to reduce the impact of the outbreak in the near term, tailored to the needs and constraints of local leaders in low- and middle-income countries. The guide and checklists were developed by a team of deeply experienced experts and former public health officials, in consultation with officials in governments and NGOs operating around the world. Our focus has been on providing information for both slowing and suppressing the spread of the virus, and also on supporting community needs in settings where long-term lockdowns may not be viable.

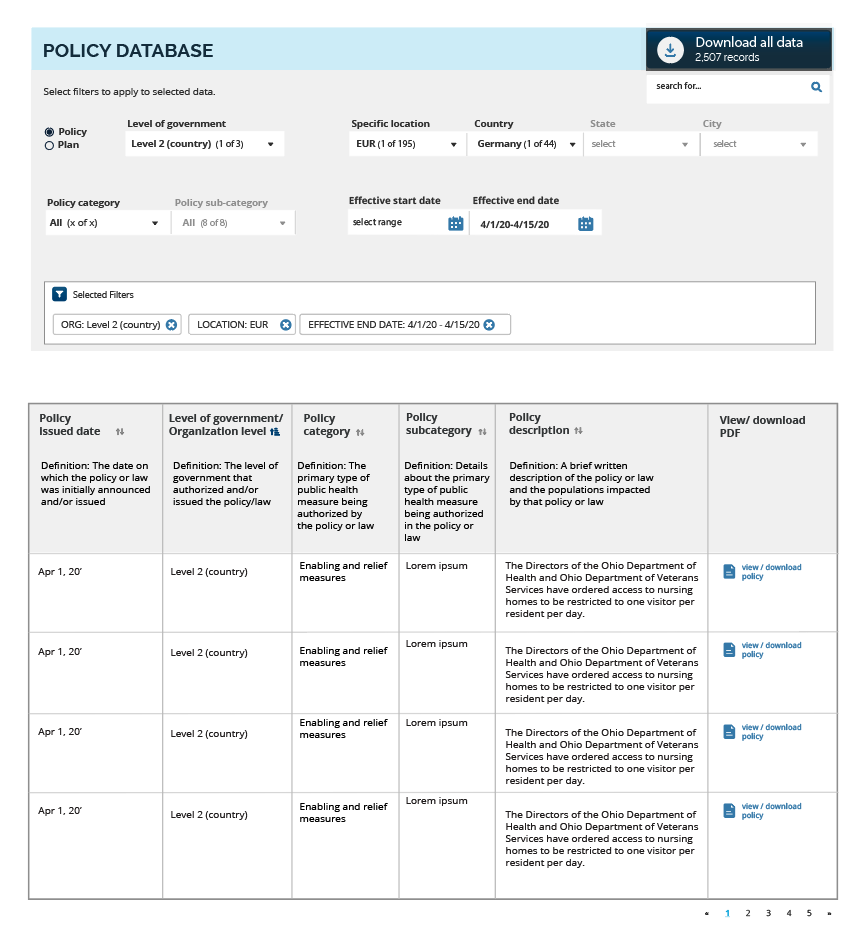

This guide is informed by existing guidance from international public health authorities, research findings, and lessons observed from countries that have been battling COVID-19 since January 2020. It is intended to complement, but not in any way supplant, advice and guidance from global, federal and local public health and other authorities.

Overview for the Guide

This guide is intended to inform and assist leaders and public officials at any sub-national level with strategy and decision-making on COVID-19 response. It is NOT a prescriptive set of instructions; rather it provides a framework and advice on how to tailor principles of outbreak control strategy, disaster management, and evolving knowledge on COVID-19 dynamics to different local conditions.

Given that this virus currently has no proven vaccines or treatments, the most important way to limit COVID-19 mortality in the near to medium term is to slow and reduce transmission – resulting in fewer cases, improving health outcomes for those who do become sick and preventing disruption to routine healthcare. However, the tactics for doing this must be tailored to the risk and capacities of every country, and may look different in high-income and low-income environments. Some pillars of response strategy in developed countries may be less feasible in low-income settings – notably prolonged “lockdowns” that greatly limit human mobility and access to labor; widespread testing; and sophisticated clinical case management. However, even where it may be difficult to reduce transmission to zero, it will be possible to significantly slow it through robust application of traditional public health measures. Some low-income settings may choose to abbreviate, adapt, or avoid the “lockdown” phase used in other countries and pivot to robust contact tracing paired with sustainable physical distancing measures and efforts to provide additional protection to high risk groups.

Measures to slow the spread of COVID-19 are vitally important, even in countries where containment may be unrealistic. COVID-19 cases requiring medical intervention are in addition to the existing healthcare demand, and experience from China, Italy, Brazil, the United Kingdom and the United States shows that unchecked spread of the virus has the potential to rapidly and abruptly overwhelm local health systems and disrupt routine care. While the world’s understanding of COVID-19 is still evolving, it is clear that the disease is many times more dangerous than seasonal flu (which has a fatality rate of approximately 0.1%). Recorded case fatality rates in various countries have ranged from more than 10% (Italy, United Kingdom, Spain) to low single digits (China, US, Germany). South Korea, which has extensive testing, has recorded a case fatality rate of approximately 2%, or 20 times as high as seasonal flu. It is important to note that these case fatality rates may be an overestimation if mild or asymptomatic cases are not part of the calculation due to low testing rates – and that high case fatality rates may themselves be an indicator of widespread transmission undetected by the existing testing infrastructure.

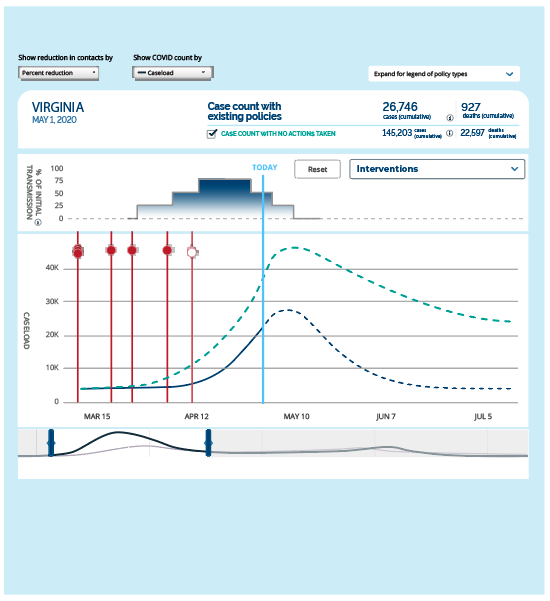

During the early phase of a local community’s COVID-19 outbreak, all elements of an initial response strategy should connect to the overarching goal of limiting deaths by reducing overall transmission. Especially in environments where healthcare access and the capacity of the existing healthcare infrastructure is limited, it is vital to reduce overall number of cases in order to minimize the number of severe cases and to ultimately reduce the number of fatalities. Delayed actions to reduce transmission allow the disease to spread widely, generating a sudden surge in critically ill cases, eroding care quality, and worsening fatality rates. The difference between these scenarios may be as little as days or weeks.

Once transmission rates have been reduced and the burden on the healthcare system has declined, it will eventually become possible to consider incrementally relaxing the range of distancing measures put in place to limit transmission.

Phases of COVID-19 in a Community

If increased transmission occurs, drastic measures may be required to contain it. These measures must be calibrated to the specific risks and capacities of the country or community. The “lockdown” approaches applied to halt explosive transmission in wealthy countries may not be replicable in developing countries, where the populations over the age of 65 are smaller, where public health and disease surveillance initiatives often rely on in-person community outreach, and where there is less ability to cushion the economic and food security shocks a lockdown imposes. Developing countries may instead pursue sustainable mitigation: scalable measures to slow transmission such as physical distancing measures and large-scale contact tracing, linked to supportive quarantine and isolation of cases and identified contacts.

While many graphics show only a single rise and fall of caseload, it is likely that there will be multiple stages of an outbreak with multiple curves, particularly in the mitigation and suppression phase following the initial surge in cases. Absent sufficient testing, effective contact tracing, and available hospital capacity, an initial plateauing or decline in cases is not sufficient basis for relaxing physical distancing or other containment measures. Communities with declining cases may suddenly see an increase due to a variety of factors including, but not limited to, an increase in testing or a change in reporting requirements, a premature relaxation of control measures, and/or importation of new cases.